Methamphetamine abuse has spread to every region of the United States in the past 10 years (Table 1).1 Its long-lasting, difficult-to-treat medical effects destroy lives and create psychiatric and physical comorbidities that confound clinicians in emergency rooms and community practice settings.

This first in a series of two articles describes methamphetamine’s growing use and offers guidance to identify abusers and manage acute “meth” intoxication. Methamphetamine-abusing patients can appear in any area of acute psychiatric practice—during emergency department (ED) evaluations, medical-surgical consultations, and inpatient psychiatric admissions. Using case examples, we describe key clinical principles to help you assess patients in each of these settings.

Table 1

10-year growth in hospitalization rates

for methamphetamine/amphetamine use*

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | 1993 | 2003 |

| U.S. national rate | 13 | 56 |

| Northeast | ||

| Connecticut | 1 | 4 |

| Maine | 2 | 5 |

| Massachusetts | <1 | 2 |

| New Hampshire | <1 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 3 | 2 |

| New York | 2 | 4 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 2 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 2 |

| Vermont | 5 | 4 |

| South | ||

| Alabama | 1 | 45 |

| Arkansas | 13 | 130 |

| Delaware | 2 | 2 |

| District of Columbia | — | 2 |

| Florida | 2 | 7 |

| Georgia | 3 | 39 |

| Kentucky | — | 20 |

| Louisiana | 4 | 21 |

| Maryland | 1 | 3 |

| Mississippi | — | 23 |

| North Carolina | <1 | 4 |

| Oklahoma | 19 | 117 |

| South Carolina | 1 | 9 |

| Tennessee | † | 6 |

| Texas | 7 | 17 |

| Virginia | 1 | 4 |

| West Virginia | <1 | — |

| Midwest | ||

| Illinois | 1 | 19 |

| Indiana | 3 | 28 |

| Iowa | 13 | 213 |

| Kansas | 15 | 65 |

| Michigan | 2 | 7 |

| Minnesota | 8 | 100 |

| Missouri | 7 | 84 |

| Nebraska | 8 | 117 |

| North Dakota | 3 | 44 |

| Ohio | 3 | 3 |

| South Dakota | 5 | 90 |

| Wisconsin | <1 | 5 |

| West | ||

| Alaska | 4 | 13 |

| Arizona | — | 36 |

| California | 66 | 212 |

| Colorado | 18 | 86 |

| Hawaii | 52 | 241 |

| Idaho | 20 | 72 |

| Montana | 30 | 133 |

| Nevada | 59 | 176 |

| New Mexico | 7 | 10 |

| Oregon | 98 | 251 |

| Utah | 16 | 186 |

| Washington | 18 | 143 |

| Wyoming | 15 | 209 |

| * Per 100,000 population aged 12 or older, with methamphetamine/amphetamine use as the primary diagnosis. Percentages in boldface exceed the national rate for that year. | ||

| † <0.05% | ||

| –No data available | ||

| Source: Reference 1 | ||

Scourge of the Heartland

A stimulant first synthesized in Japan,2 methamphetamine is the primary drug of abuse in Asia3 and the leading drug threat in the United States, according to U.S. law enforcement officials.4 Although most methamphetamine used in the United States is manufactured in “super-labs” along the U.S.-Mexican border,4 the drug is also easily made from common ingredients in small-scale home laboratories.

These smaller domestic “meth labs” have devastated rural communities and altered demographic patterns of methamphetamine abuse (Figure 1).5 Two aspects of rural life—relative isolation and availability of ingredients for production—proved critical in the initial spread of methamphetamine production and use in the United States. As a result, production by smaller labs is being targeted by state and federal law enforcement officers, who have had some success in eradicating this scourge (Box 1, Figure 2).6-9

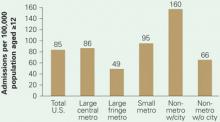

Figure 1 Substance abuse treatment admission rates

for methamphetamine-related diagnoses

Substance abuse treatment centers in rural areas had the highest admission rates for methamphetamine/amphetamine-related diagnoses in 2004. Admission rates in nonmetropolitan regions containing cities with populations >10,000 were triple those of suburbs, nearly twice those of big cities, and twice the U.S. average.

Figure 2 Methamphetamine clandestine laboratory incidents,* 2005

* Incidents include chemicals, contaminated glass, and equipment used in methamphetamine production found by law enforcement agencies at laboratories or dump sites.

Source: Drug Enforcement Administration database, reference 9Box 1

Dangerous recipes. The ease with which methamphetamine can be “cooked” in a home kitchen from ingredients available in pharmacies and hardware stores has contributed to the drug’s rapid spread. Meth users produce their own “fixes” using recipes readily available on the Internet and passed on by other “cooks.”6 The combination of inexperienced or intoxicated cooks, homemade equipment, and highly flammable ingredients results in frequent fires and explosions, often with injuries to home occupants and emergency responders.7

Meth labs have been estimated to produce 6 pounds of toxic waste for each 1 pound of methamphetamine produced. Composed of acid, lye, and phosphorus, this waste typically is dumped into ditches, rivers, yards, and drains. The fine-particulate methamphetamine residue generated during home production settles on exposed household surfaces, leading to absorption by children and others who come into contact with it.6,8

Disastrous results. Methamphetamine cooking has caused a social, environmental, and medical disaster—particularly in the Midwest (Figure 2), although the situation has improved in the past 2 years. Many states have passed laws restricting and monitoring sales of the methamphetamine ingredients ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. A change in U.S. law prohibiting pseudoephedrine imports in bulk from Canada has decreased domestic “superlab” production.9 Although these laws appear to have slowed U.S. manufacturing, the drug is still readily available, predominantly smuggled in from large-scale producers in Mexico.

Symptoms of ‘Meth’ Use

Physiologic effects. Methamphetamine is taken because it induces euphoria, anorexia, and increased energy, sexual stimulation, and alertness. Initial use evolves into abuse because of the drug’s highly addictive properties. Available in multiple forms and carrying a variety of labels (see Related resources), methamphetamine causes CNS release of monoamines—particularly dopamine—and damages dopaminergic neurons in the striatum and serotonergic neurons in the frontal lobes, striatum, and hippocampus.10,11

Through sympathetic nervous system activation, methamphetamine can cause reversible or irreversible damage to organ systems (Table 2).12-17

Table 2

Physiologic signs of methamphetamine abuse

| Vital signs | Tachycardia |

| Hypertension | |

| Pyrexia | |

| Laboratory abnormalities | Metabolic acidosis |

| Evidence of rhabdomyolysis | |

| Organ damage | Cardiomyopathy |

| Acute coronary syndrome | |

| Pulmonary edema | |

| Stigmata of chronic use | Premature aging |

| Cachexia | |

| Discolored and fractured teeth | |

| Skin lesions from stereotypical scratching related to formication (“meth bugs”) and/or compulsive picking | |

| Source: References 12-17 | |

Psychiatric effects. Methamphetamine abusers frequently report depressive symptoms, including irritability, anxiety, social isolation, and suicidal ideation.10,18 These patients may show: