Dreams are a rich resource for understanding how the mind integrates waking experience into older memory networks. Any psychiatrist who doubts dreams’ therapeutic value has probably not attended closely to his or her own dreams or become aware of exciting new evidence.

Recent understandings of how memory is processed during sleep are bringing dreams back into clinical importance. Patients can gather clinically useful data while sleeping—not in laboratories but in their own beds. Detecting and interpreting patterns in that data can help you treat patients not responding adequately to other therapies.

CHARTING DREAM SEQUENCES

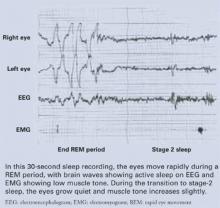

The rate at which the eyes move during rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep (Figure) has been associated with memory consolidation. Eye movements increase during REM sleep, and waking performance improves after intensive learning periods. When eye movements are sparse, patients report dreams with less visual imagery and blander emotional content.1

Though all sleep stages contribute to learning and memory, REM sleep appears to allow wider, easier access to memories2 than does slow-wave sleep or waking. In other words, dreams are far from meaningless. They constitute a continuing mental operation that allows us to modify memory networks of emotional importance to us.

Dreams’ emotional tone tends to shift from negative to positive as the night goes on:3

- Dream-to-dream down-regulation of negative feelings is seen when a person’s waking concerns are strong but not overwhelming.

- Conversely, a dream sequence may show no progress within the night4—and the last dream may be as negative as the first—if the person has reached a point of resignation while awake.

This “sequential hypothesis”5 holds that knowledge of dreams as they occur—one after the other within the night—is a valuable resource for observing how a person is relating waking experience to the past. Dreams thus can give the therapist a “heads up” about a patient’s progress in organizing troublesome feelings.

Figure REM sleep: Dreaming’s prime time

CASE EXAMPLE: NIGHTMARES FOR 13 YEARS

Ms. R, a newlywed at age 30, presents for help with repetitive nightmares that prevent her from sharing a bed with her husband. She was raped at age 17 and has suffered nightmares since then. Once or more nightly she dreams of being attacked and awakens in terror, with profuse sweating. She usually has to change her nightclothes and sometimes the sheets.

Her therapist gives Ms. R four rules—the RISC method6—for shifting her dreams from negative to positive:

- Recognize that the dream is not going well.

- Identify what about it is frightening.

- Stop the dream, even if she must force her eyes open.

- Change the action to something positive.

At the third therapy session, Ms. R reports she had a successful dream. She was lying on her back on an open elevator platform. The elevator was rising dangerously high over the cityscape. She realized she was afraid and got up to see what was happening. As she arose, the elevator walls rose up to protect her. The patient says she learned if she “stands up for herself” all would be well.

After two more sessions with successful practice of this skill, she terminates therapy. When called 1 year later, she says she is expecting a child and has only an occasional nightmare, which she feels she can handle.

CLINICAL USES OF DREAM THERAPY

Dream interpretation may help us understand emotional programs that underlie patients’ unsatisfactory waking behavior. For example:

- Victims of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as Ms. R may suffer repetitive nightmares with recurrent themes and excessive negative feelings. We can encourage them to shift their dream scripts from negative to positive.7

- Uninsightful, alexythymic patients, who often leave treatment before deriving any benefit, may learn to understand themselves by becoming aware of their dreams.8

- Severely depressed patientsoften have limited dream recall during sleep studies—even when every REM period is interrupted. They may be taught to improve their dream recall.9

Rules for improving dream recall are few, simple, and effective when the sleeper is motivated to remember them (Box). Just as one can learn to awaken before the morning alarm clock goes off, patients can learn to awaken to recall a dream.

After you have enough of a patient’s dreams to work from—20 is a good start—look for repeated dimensions that are the dreams’ building blocks.5 Look for polar opposites—such as safe-at risk, foolish-clever, exposed-hidden, strong-weak, attractive-ugly—that describe major characteristics of the self figure. Each has a positive or negative emotional value that can be explored.

Go to sleep intending to remember a dream as you awaken.

Sleep until you wake up naturally.* Spontaneous awakening is likely to be from REM sleep, which is dominant in the last third of the night.

Once awake, lie perfectly still. Do not jump up or open your eyes. This preserves a REM-like state when attention is focused inward, not on outside stimuli, and motor tone is profoundly reduced.

Rehearse the recalled images, and give the theme a title (“I left my briefcase on the train” or “My husband returned from a trip unexpectedly”), which makes dream details easier to recall.

Write or tape record all that you can remember, noting the date and time of the report.

Add a note about anything the dream brings to mind about your thoughts before sleep.

* To allow spontaneous awakening, practice dream recall when you do not have to wake up to an alarm clock, such as on weekends.