Current antipsychotics are reasonably effective in treating positive symptoms, but they do less to improve the negative and cognitive symptoms1 that contribute to patients’ long-term poor functional capacity and quality of life.2 So what do psychiatrists do in clinical practice to mitigate antipsychotics’ limitations? We augment.

Schizophrenia patients routinely are treated with polypharmacy—often with antidepressants or anticonvulsants—in attempts to improve negative symptoms, aggression, and impulsivity.3 Most adjuncts, however—including divalproex, antidepressants, and lithium—have shown very small, inconsistent, or no effects.4,5 The only agent with a recent meta-analysis supporting its use as augmentation in treatment-resistant schizophrenia is lamotrigine,6 an anticonvulsant approved for use in epilepsy.7

This article examines the evidence supporting off-label use of lamotrigine as an augmenting agent in schizophrenia and explains the rationale, based on lamotrigine’s probable mechanism of action as a stabilizer of glutamate neurotransmission.

Is lamotrigine worth trying?

Some 20% of schizophrenia patients are considered treatment-resistant, with persistent positive symptoms despite having undergone ≥2 adequate antipsychotic trials.8 Evidence suggests clozapine then should be tried,4 but approximately one-half of treatment-resistant patients do not respond to clozapine. Treatment guidelines are limited for these 10% of schizophrenia patients with an inadequate response to available therapies, including clozapine.4

In a meta-analysis of 5 controlled trials in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, adjunctive lamotrigine was shown to significantly reduce Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores, positive symptom subscores, and negative symptom subscores.6 In these trials, lamotrigine was added to various antipsychotics, including clozapine. Based on the results—as outlined below—we suggest:

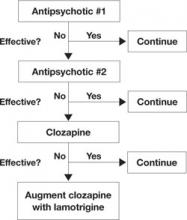

- In treatment-resistant patients with residual symptoms while taking clozapine, lamotrigine given in dosages ≥200 mg/d could be a first-line adjunct (Figure 1).

- Lamotrigine augmentation also might help patients whose positive symptoms are adequately controlled but who have persistent negative and/or cognitive symptoms.

- Evidence does not support routine use of lamotrigine in patients taking antipsychotics other than clozapine.

Managing side effects. Lamotrigine is generally well tolerated; in the meta-analysis, nausea was the only side effect more common with lamotrigine (9%) than with placebo (3.9%).6 Close follow-up is required, however, as a few case reports have noted worsening positive symptoms when lamotrigine was added to antipsychotics.9,10

Lamotrigine produces a skin rash in approximately 10% of patients; the rash usually is benign but may be severe, including the potentially fatal Stevens-Johnson syndrome.11 In the meta-analysis, rash was no more likely in patients receiving placebo (3%) than those receiving lamotrigine (2.2%), and no serious rashes were reported.6 Even so, lamotrigine needs to be titrated upwards very slowly over weeks, and patients must be able to monitor for rash.

Figure 1 An evidence-based approach to treatment-resistant schizophrenia

Treatment-resistant schizophrenia is defined as residual positive symptoms after ≥2 adequate antipsychotic trials. Evidence supports trying clozapine as the next step.4 When patients show an inadequate response to clozapine, a meta-analysis of 5 controlled trials6 indicates that lamotrigine may be a useful first-line adjunct.

Why consider lamotrigine?

During clinical trials of lamotrigine for epilepsy, patients showed improved mood12 as is seen with other anticonvulsants such as valproate and carbamazepine.13 A series of randomized trials then demonstrated lamotrigine’s effectiveness in treating patients with bipolar I disorder, especially during depressive episodes,14,15 and the FDA approved lamotrigine for maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder.16 In those early studies, lamotrigine also improved bipolar patients’ quality of life and cognitive function in addition to showing mood-stabilizing properties.12

The glutamate hypothesis. Lamotrigine is an inhibitor of voltage-gated sodium channels and has been shown to inhibit the excessive synaptic release of glutamate.17 Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter for at least 60% of neurons in the brain, including all cortical pyramidal neurons. A large body of evidence implicates dysfunctional glutamate signaling in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.18

For example, phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine—antagonists of one subtype of glutamate receptor, the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor—are well known to produce positive psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive dysfunction.19 This led to a long-held hypothesis that schizophrenia is caused by too little glutamate. However, ketamine and PCP also increase the release of glutamate at synapses that then can act on glutamate receptors other than the NMDA receptor, which suggests that too much glutamate also may be involved in schizophrenia.

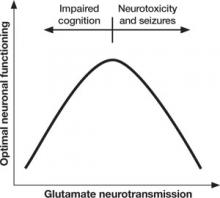

Too little or too much glutamate? These competing hypotheses could both be at least partially true, suggesting an “inverted-U” pattern of glutamate signaling (Figure 2). Because glutamate is involved in most cortical functions, too little glutamate can cause cognitive and processing deficits such as those seen in schizophrenia. On the other hand, too much glutamate can be toxic to neurons and may be a factor in neurodegeneration, such as in Alzheimer’s disease.20 Indeed, schizophrenia may be associated with gradual neurodegeneration.21