Eight weeks after his wife died from an unexpected illness, Mr. M, age 55, remains overwhelmed, disconsolate, and virtually incapacitated. Previously in good health and a successful accountant, he struggles with low mood, guilt, anxiety, and anhedonia and is troubled by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. “My life has been turned upside down,” he says.

His primary care physician’s support and encouragement—along with hypnotics, an anxiolytic, and antidepressants—have done little to improve his sleep and mood or relieve his emotional suffering. Mr. M has resumed work for financial reasons but returns home exhausted and demoralized, shunning the few friends who call. He has no history of a mood disorder or substance abuse. He has never expressed suicidal or homicidal ideation and shows no evidence of psychotic symptoms. He is referred to a psychiatrist for what his physician regards as a treatment-resistant depression.

When a patient’s symptoms seem disproportionate to apparent stressors, I call this presentation a patient’s predicament: a unique, profoundly unsettling, but poorly understood misgiving that something is wrong—perhaps terribly so—and that life may never be the same again (Table). Emotional flooding typically overwhelms these patients, and they are unable to express what they are experiencing.

For mental health professionals, the concept of a predicament is useful when working with patients who are moderately to severely ill or facing a life-diminishing or life-threatening illness.

Table

Patient in a predicament? Look for these 6 clues

| Shows an unusual, disproportionate, or prolonged response to a distressing experience |

| Is incapacitated by persistent suffering and misery |

| Expresses feelings of drastic personal change, turmoil, life disruption, or hopelessness |

| Describes feeling lost, bewildered, and helpless or shows behavioral equivalents (such as aimlessness, loss of purpose) |

| Experiences difficulty achieving or maintaining an expected response to conventional and evidence-based treatment in the absence of psychosis |

| Demonstrates a clinical course punctuated by noncompliance with treatment that suggests the patient may have given up or feels unworthy of relief |

Affected by a ‘field of forces’

I conceptualize Mr. M’s unrelieved suffering as resulting from 1 or more threats—typically not fully appreciated by the patient—to important elements that undergird and sustain his sense of self. A predicament can be related to:

- Eric Cassell’s conception of suffering that accompanies threats to an individual’s sense of “personhood” in terms of its many domains1

- Thomas Merton’s concept of emotional destabilization caused by threats to a person’s “false self”2

- William Shaver’s concept of a person’s fragile “illusory self” and threats to “safety zones” that protect it.3

Patients experience a predicament as an emotional perturbation caused by something that has happened to them or is evolving from an acute loss, trauma, acute or chronic illness, unpleasant occurrence, or a recommended medical intervention. A predicament may embody multiple dimensions (biological, psychological, interpersonal, familial, occupational, spiritual, existential, economic, ethnic, and cultural).

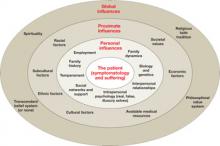

Extrapolating from a social science concept, these dimensions comprise a “field of forces”—the interplay of internal and external, proximate, and global factors—that act on an individual (Figure). These forces:

- contribute to a person’s sense of self and shape the manner in which that self is manifested to others—including the attending physician

- do not invalidate or discount the importance of the patient’s transference but may cloud it and render it less “transparent.”

Treatment resistance? A biomedical intervention focused on symptoms or a prominent symptom complex may be partially effective but result in a lowered threshold for recurrences. Although both patient and psychiatrist feel relief when symptoms abate, the individual is not necessarily healed. The disorder may continue to affect the patient, his family, his work performance, or other aspects of life.

One might conclude that this is a “treatment-resistant” depression or a “difficult patient” who has somehow not responded as anticipated. Yet, as author Norman Cousins observed from his experience with life-threatening illness, “patients are a vast collection of emotional needs, and understanding how patients are affected by serious illness as well as the illness itself paves the way for communicating without crippling the patient.”4

Figure A predicament comprises an interactive ‘field of forces’

The patient resides at the epicenter of inborn and external factors that make up his or her interactive, multidimensional environment. Concentric rings convey the interplay of personal, proximate, and global influences with which the patient must cope, whether or not he or she is aware of these influences.

Exploring the predicament

By sensitively exploring the personal story behind the patient’s presenting symptoms (the predicament the patient is in), you become a nonjudgmental, affirming witness to that story. Simultaneously, you can urge the patient to consider how he or she might have arrived at the state of feeling overwhelmed (a process of demystification and early insight aptly described by psychotherapist Anthony Storr as “making the incomprehensible comprehensible”5).