History: shop talk

Ms. B, age 46, presents to the ER at her brother’s insistence. For about 6 months, she says, she has been “hearing voices”—including that of her boss—talking to each other about work.

Ms. B has no personal or family psychiatric history but notes that her sister died 6 months ago, and her father died the following month. At work, she is having trouble getting along with her boss. She adds that she has been skipping church lately because she believes her church is under investigation and the inquiry might be targeting her.

Ms. B has been a company manager for 20 years. She is divorced, has no children, and lives alone. She says she does not smoke or use illicit drugs and seldom drinks alcohol. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, depressed mood, or visual hallucinations. She says she is sleeping only 3 to 4 hours nightly and feels fatigued in the afternoon. She denies loss of concentration or functioning.

Mental status. Ms. B is well groomed, maintains good eye contact, and is superficially cooperative but increasingly guarded with further questioning. She describes her mood as “OK,” but her affect is blunted. Thought process is logical but circumstantial at times, and her thoughts consist of auditory hallucinations, paranoid thinking, persecutory delusions, and ideas of reference. She has poor insight into her symptoms and does not want to be admitted.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are unremarkable. Negative ethanol and urine drug screens rule out substance abuse, and preliminary noncontrast head CT shows no acute changes.

The author’s observations

In women, schizophrenia typically emerges between ages 17 and 37;1 onset after age 45 is unusual.2 Ms. B’s age, family history, and lack of a formal thought disorder or negative symptoms make late-onset schizophrenia unlikely, though it cannot be ruled out.

Ms. B denies mood symptoms, but significant stressors—such as the recent deaths of her sister and father and difficulties at work—could precipitate a mood disorder. Of the possible diagnoses, major depressive disorder is most likely at this time.1,3 Because Ms. B’s symptoms do not clearly match any diagnosis, we speak with her brother and sister-in-law to seek collateral information.

Collateral history: beware of spies

Ms. B’s brother says his sister began behaving strangely about 8 months ago and has worsened lately. He says she suspects that her boss hired spies to watch her house, car, and her parent’s house. After work, she often parks in paid garages rather than at home to avoid being “followed.” When visiting, he says, she leaves her keys outside because she fears they contain a tracking device. Family members say Ms. B sometimes drops by at night—as late as 5 AM—complaining that she cannot sleep because she is being “watched.”

Ms. B’s family hired a private investigator 3 or 4 months ago to examine her house and car. Although no tracking devices were found, her brother says, Ms. B remains convinced she is being followed. He says she often speaks in “code” and whispers to herself.

According to her brother, Ms. B often hears voices while trying to sleep, saying such things as “Why won’t she turn over?” She reportedly wears a towel while showering because the “spies” are watching. During a conference she attended last week, she told her brother that a group of government investigators followed her there and arrested her boss.

Ms. B’s sister-in-law says the patient’s functioning has declined sharply, and that she has been helping Ms. B complete routine work. Neither she nor Ms. B’s brother have noticed a change in the patient’s energy, productivity, or speech production or speed, thus ruling out bipolar disorder. Ms. B’s brother confirms that there is no family history of mental illness.

The author’s observations

Collateral information about Ms. B points to psychosis rather than a mood disorder with psychotic features, but she lacks the formal thought disorder and negative symptoms common in primary psychotic disorders.

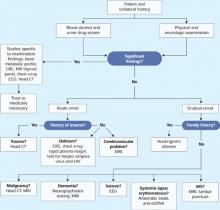

Because Ms. B’s presentation is atypical, we order brain MRI to check for a general medical condition (Figure 1). If brain MRI suggests a medical problem, we will follow with EEG, lumbar puncture, or other tests.

Figure 1 Clinical steps to rule out medical causes of late-onset psychosis

treatment, testing: what mri suggests

We admit Ms. B to the locked inpatient psychiatric unit—where she remains paranoid and guarded—and prescribe risperidone, 1 mg/d, to address her paranoia. She refuses medication at first because she feels she does not need psychiatric care, but we give her lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d for her anxiety, along with psychoeducation and family support. After 3 days, we stop lorazepam and Ms. B agrees to take risperidone.