What do you tell your patients who are self-medicating with herbal remedies? Can dietary supplements safely improve mood disorders, insomnia, and other psychiatric complaints?

Evidence is limited on complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), their active components, pharmacokinetics/dynamics, adverse effects, drug interactions, and therapeutic outcomes. Based on our review of trial data, case reports, and an NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) survey,1 we offer information to help you:

- identify patients using dietary supplements

- avoid serious interactions with common psychotropics

- counsel patients on the efficacy and safety of ginkgo biloba, St. John’s wort, kava kava, and valerian (Table 1).

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ASK

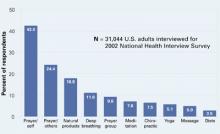

One-third of Americans who took part in the NCCAM survey reported using CAM. After prayer—the number-one CAM—respondents said they most often used natural products such as herbals, botanicals, nutraceuticals, phytomedicinals, and dietary supplements (Figure).1

Table 1

4 herbal supplements with purported psychotropic effects

| Herb | Promoted use | Safety | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo biloba | Dementia, memory | Bleeding complications, drug interactions a concern | Some data support a trial in dementia; beware of safety concerns |

| St. John’s wort | Depression | Substantial drug interactions | Use not recommended because of wide-ranging drug interactions |

| Kava kava | Anxiety | Hepatotoxicity risk, drug interactions; off market in Europe and Canada | Use not recommended because of safety issues |

| Valerian | Insomnia | Limited data available | Benign (?); monitor for possible adverse events or drug interactions |

Patients tend to use CAM to treat chronic medical conditions such as back pain, depression, and anxiety.1 Although CAM use is common, only 38% of patients say they disclose using CAM to their physicians.2 These use and disclosure patterns are similar in psychiatry.3

Herbal products may produce symptoms that mimic those of mental illnesses, such as psychosis and mania, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Abruptly stopping some herbs can produce withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen with benzodiazepine and antidepressant cessation. Supplements also can inhibit or augment prescribed psychotropics’ effects, and notable consequences include the potential for serotonin syndrome with use of St. John’s wort.

The key to learning about a patient’s use of dietary supplements is to ask. Patients commonly say they do not tell their doctors about using dietary supplements because “it wasn’t important for the doctor to know” or “the doctor never asked.”4,5 Ten tips for discussing nutritional supplements with patients are shown in the Box.

Buyer—and psychiatrist—beware. Because of dietary supplements’ regulatory status, physicians and patients need to learn as much as they can about these products’ documented safety and efficacy. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act passed by Congress in 1994 does not require manufacturers to prove their products are safe or effective before marketing them. They also can make claims that suggest uses in physical/emotional structure and function, such as “helps maintain a healthy emotional outlook.”

The FDA bears the burden of proof regarding safety and can remove a dietary supplement from the market only after receiving documented adverse event information from the public.6 The FDA has confiscated herbal products containing prescription drugs and misidentified herbal components.

GINKGO BILOBA FOR DEMENTIA

Ginkgo biloba was the third most commonly used herbal product (21%) in the NCCAM survey. Ginkgo is promoted primarily for dementia, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and memory enhancement. The standardized ginkgo extract (EGb 761) contains several components to which its pharmacologic activity has been attributed. Its constituents are thought to act primarily through anticoagulant effects by inhibiting platelet-activating factor and cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase. They also act through membrane stabilization, antioxidant properties, free-radical scavenging, and inhibition of beta-amyloid deposition.7

Efficacy. In patients with dementia, clinical trials using EGb 761 have shown small improvements in or maintenance of cognitive and social functioning, compared with placebo.8,9 The clinical significance of these findings is unclear, however. Ginkgo’s usefulness in enhancing memory is less certain. Controlled clinical trials are evaluating ginkgo’s efficacy in various conditions.10

Adverse effects. Bleeding complications are the primary concern with ginkgo biloba use, and caution is urged when it is taken concomitantly with aspirin or other antithrombotic drugs. Patients receiving warfarin should not take ginkgo because of the combined antiplatelet effects and ginkgo’s inhibition of warfarin metabolism and elimination.

Drug-herb interactions. One report showed that EGb 761 is a strong inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 2C9 enzyme system (CYP 2C9).11 Other identified inhibitors of CYP 2C9 are fluvoxamine (strong inhibitor), amiodarone, cimetidine, fluoxetine, and omeprazole. Drugs that serve as substrates for that system and can have decreased clearance include phenytoin, warfarin, amitriptyline, and diazepam;12 use caution, therefore, when you co-administer these drugs with ginkgo.

Figure 10 CAM therapies patients report using most often

CAM: Complimentary and alternative medicines

Source: Barnes T, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 27, 2004: Advance Data Report #343 (available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad343.pdf) Dosage. The usual dosage for standardized ginkgo extract is 120 to 240 mg/d, given in divided doses. Improvements associated with ginkgo use usually are seen within 4 to 12 weeks after starting therapy.7 Consider discontinuing therapy if you see no results after that time. Little is known about ginkgo’s effect after 1 year of use.