Aggression, irritability, repetitive phenomena, or hyperactivity can interfere with the education and treatment of patients with autism.1 To assist clinicians in selecting drug therapies to control these behaviors, we developed a medication strategy based on controlled studies and our experience in an autism specialty clinic. In this article, we:

- offer an overview with two algorithms that show how to target maladaptive behaviors in patients of all ages with autism

- and discuss the controlled clinical evidence behind this approach.

Targeting behaviors

A multimodal approach is used to manage autistic disorder. Although behavioral techniques are useful and may decrease the need for drug therapy, one or more medications are often required to target severe maladaptive behaviors. Although we recommend that you consider all interfering behaviors when selecting medications, it is important to:

- initially focus on symptoms—such as self-injurious behaviors and aggression—that acutely affect the patient’s and caregiver’s safety

- consider the patient as being pre- or postpubertal, as developmental level may affect medication response.

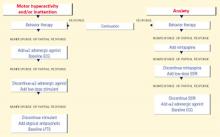

Figure 1 BEHAVIOR-BASED DRUG THERAPY FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM

Source: Reprinted with permission from McDougle CJ, Posey DJ. Autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. In: Martin A, Scahill L, et al (eds). Pediatric psychopharmacology: principles and practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Aggression or self-injury. When drug therapy is needed to control severe aggression or self-injurious behavior, we recommend a trial of an atypical antipsychotic for prepubertal patients (Figure 1). Alternately, you may consider a mood stabilizer such as lithium or divalproex for an adult patient with prominent symptoms (Figure 2). However, mood stabilizer use requires monitoring by venipuncture for potential blood cell or liver function abnormalities.

Atypical antipsychotics are associated with adverse effects including sedation, weight gain, extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and hyperprolactinemia. Therefore, you may need to monitor weight, lipid profile, glucose, liver function, and cardiac function when using this class of agent.

Repetitive phenomena can be addressed with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although SSRIs may be activating in children and tend to be better tolerated in older adolescents and adults.

Anxiety. In children with anxiety, we suggest a trial of mirtazapine—because of its calming properties—before you try an SSRI. If both the SSRI and mirtazapine are ineffective, try an α2-adrenergic agonist. A baseline ECG is recommended before starting an α2-adrenergic agonist—particularly clonidine, which has been associated with rare cardiovascular events. Overall, these agents are well tolerated.

Hyperactivity, inattention. Anecdotal evidence indicates that stimulants may worsen symptoms of aggression, hyperactivity, and irritability in individuals with autism. Therefore, we suggest you start with an α2-adrenergic agonist when target symptoms include hyperactivity and inattention. Consider a stimulant trial if the α2-adrenergic agonist does not control the symptoms.

An atypical antipsychotic is generally recommended for autistic individuals with treatment-resistant hyperactivity and inattention, anxiety, and interfering repetitive behaviors.

Drug therapy. As summarized below, controlled evidence for behavior-based drug therapy of autism (Table.) suggests a role for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and psychostimulants in managing interfering behaviors.

Antipsychotics

Risperidone. Two controlled studies have reported the effect of risperidone on autism’s related symptoms.

McDougle et al conducted a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone, mean 2.9 mg/d, in adults with pervasive developmental disorders.2 Repetitive behavior, aggression, anxiety, irritability, depression, and general behavioral symptoms decreased in 8 of 14 patients, as measured by Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Sixteen subjects who received placebo showed no response. Transient sedation was the most common adverse effect.

More recently, the National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone, 0.5 to 3.5 mg/d (mean 1.8 mg/d), in 101 children and adolescents with autism.3 After 8 weeks, 69% of the risperidone group responded, compared with 12% of the placebo group. Response was defined as:

- at least a 25% decrease in the Irritability subscale score of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC)

- and CGI ratings of “much improved” or “very much improved.”

Risperidone was effective for treating aggression, agitation, hyperactivity, and repetitive behavior. Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 2.7 kg vs. 0.8 kg with placebo), increased appetite, sedation, dizziness, and hypersalivation.

Olanzapine. A 12-week, open-label study of olanzapine, mean 7.8 mg/d, was conducted in eight patients ages 5 to 42 diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder.4 Hyperactivity, social relatedness, self-injurious behavior, aggression, anxiety, and depression improved significantly in six of seven patients who completed the trial, as measured by a CGI classification of “much improved” or “very much improved.” Adverse effects included weight gain (mean 18.4 lbs) in six patients and sedation in three.