Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2011/01/bariatric-procedures-managing-patients.html#comments

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for obesity (defined as a body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) and is recommended for extremely obese individuals (BMI >40 kg/m2) age >18.1,2 Most patients experience significant weight loss accompanied by improvements in mood, physical comorbidities, and quality of life (Box).3-8 Despite these favorable outcomes, several aspects of postoperative care—such as management of mental health issues—remain unclear. Bariatric surgery candidates show high rates of preoperative psychopathology, particularly depression and dysphoria. Little is known about how bariatric surgery affects absorption of psychiatric medications, leaving prescribing clinicians with minimal guidance when a postoperative patient reports changes in mood symptoms.

This article discusses the psychosocial status of bariatric surgery candidates and presents a rationale for increased medication monitoring after surgery.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvements in obesity-related comorbidities, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and decreased mortality.3,4

Many patients are able to reduce or discontinue many of their nonpsychiatric preoperative medications as their comorbid conditions improve.5 Symptoms of depression and anxiety, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, and body image often improve dramatically in the first year after surgery and endure for several years.6,7

Psychosocial improvements, however, may not translate into changes in psychotropic use. In a sample of 114 bariatric surgery patients, 43% were taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor before surgery, 40% at 12 months postsurgery, and 31% at 24 months.8 These percentages do not account for patients who were taking other types of antidepressants.

Surgical treatment of obesity

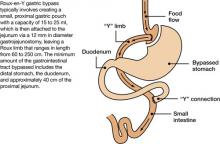

The most common surgical procedures for weight loss are adjustable gastric banding (AGB) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); each can be performed laparoscopically. With both procedures, food intake is restricted by creating a gastric pouch at the base of the esophagus. RYGB (Figure)9,10 also is thought to induce weight loss through selective malabsorption and favorable effects on gut peptides11,12 and currently is the procedure of choice in the United States.13

Figure Roux-en-Y: Bariatric procedure of choice

Source: References 9,10Bariatric surgery patients typically lose 25% to 35% of their initial body weight within 12 to 18 months of surgery.3,4 However, 20% to 30% of patients fail to achieve typical postoperative weight loss or regain large amounts of weight within a few years.14-16 Suboptimal results have been attributed to multiple factors, including problematic dietary intake, disordered eating, low levels of physical activity, preoperative psychopathology, and poor follow-up.6,17,18

Preop psychopathology

Twenty percent to 60% of extremely obese persons who pursue bariatric surgery have a psychiatric illness.6,7 In a study of 288 bariatric surgery candidates assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSMIV, 38% received a current axis I diagnosis and 66% were given a lifetime diagnosis.19 In a separate study of 174 individuals seeking bariatric surgery, 24% met criteria for a current axis I or axis II disorder and 37% were found to have ≥1 lifetime diagnoses.20 The most common lifetime diagnoses were affective disorders (22%), anxiety disorders (16%), and eating disorders (14%).20

Psychopathology could negatively impact postoperative outcome. In an observational study, patients with a lifetime diagnosis of any axis I disorder—particularly mood and anxiety disorders—experienced less weight loss 6 months after RYGB compared with those who never received an axis I diagnosis.21 Bariatric surgery patients with ≥2 psychiatric diagnoses were more likely to stop losing weight or regain weight after 1 year compared with those with 1 or no diagnosis.22 Psychiatric illness also appears to impact longer term weight loss.23

Most bariatric surgery programs in the United States require a mental health evaluation as part of the patient selection process.24 These assessments may include evaluating a patient’s behavior patterns, motivation, expectations, and cognitive and emotional functioning, and performing psychological testing (see Related Resources). Psychiatric problems such as substance abuse, active psychosis, bulimia nervosa, and severe, uncontrolled depression1,9,25 are widely considered contraindications to bariatric surgery.24,26

Postsurgery considerations

At the time of bariatric surgery 16% to 40% of patients are receiving mental health treatment, which often includes antidepressants.27-29 Unfortunately, little is known about how medications interact with these surgical procedures. Dramatic changes in medication absorption may occur because of reduced gastrointestinal (GI) surface area. Rapid reduction in body weight and fat mass and postoperative complications also may impact the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants.

Pharmacokinetics. Anatomic and physiologic changes with bariatric surgery may lead to changes in the pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of certain medications, particularly after RYGB. PK studies typically are conducted by collecting a series of plasma samples at predetermined intervals after a patient takes a medication. The blood levels of the medication and its active metabolites are used to compute multiple PK parameters that illustrate drug absorption, distribution, and metabolism. Theoretically, a bariatric surgery patient may experience changes in the rate and/or extent of: