Many catatonia cases respond to benzodiazepines—especially lorazepam—but up to 30% do not. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can be effective, but what’s the next step when ECT is unavailable or inappropriate for your patient?

To help you solve this dilemma, we describe our diagnosis and treatment decisions for a patient we call Mr. C. We explain how our process was guided by recent understandings of an abnormal neural circuit that appears to cause catatonia’s complex motor and behavioral symptoms.

This article describes that neurologic pathology and answers common questions about the clinical workup and treatment of catatonia.

CASE: TROUBLE IN TV LAND

Mr. C, age 69, caused a disturbance at a local TV station, demanding that they broadcast a manuscript he had written. Police took him to a local hospital, where he was stabilized and then transferred to a neuropsychiatric hospital for evaluation.

The psychiatric interview revealed that he had developed insomnia, excessive activity, and delusional thinking 2 weeks before admission. His medical history included coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension, and hypothyroidism. Medications included thyroid hormone replacement therapy, furosemide, potassium, ranitidine, simvastatin, metoprolol, and lisinopril. CAD treatment included stent placement and nitroglycerin as needed.

He had been hospitalized in his 30s and treated with ECT for what he called “bad thoughts.” He said he improved after 1 month and had no subsequent psychiatric history. He denied drug or alcohol abuse.

Shortly after admission, he refused to eat or drink and after 1 week became dehydrated. He also showed mutism, immobility, and stupor. He was transferred to the medical service for IV rehydration.

MANY SCENARIOS AND SIGNS

Mr. C’s symptoms suggest possible catatonia, a neuropsychiatric syndrome of motor dysregulation found in up to 10% of acutely ill psychiatric inpatients.1,2 A movement disorder,1,2 catatonia occurs with general medical conditions and psychiatric disorders (Table 1).

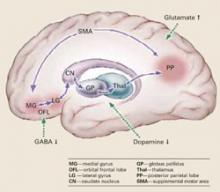

Pathophysiology. Catatonic signs develop when aberrant signals from neurochemical abnormalities trigger a neural circuit that affects the medial gyrus of the orbital frontal lobe, the lateral gyrus, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus, and thalamus (Box).3-5

Presentation. A focused exam is required because patients with catatonia often do not provide a comprehensive or reliable history.2 They show mutism, characteristic postures, rigidity, aberrant speech, negativism, and stereotyped behaviors.1,2 They may present in an excited or retarded state:

- Excited patients may injure themselves or others and develop hyperthermia, tachycardia, and elevated blood pressure from excessive motor activity.

- Patients in a retarded state may present with bradykinesia and poor self-care. They may be unresponsive to external stimuli, develop catatonic stupor, and refuse to eat or drink.

Mr. C’s earlier insomnia, excessive activity, and delusional thinking (such as the TV station incident) may have signaled an excited catatonia. On admission to the medical service, however, he presented in a retarded state.

Signs. Part of the challenge with detecting catatonia’s signs is that there are so many; some rating scales list more than 20. Not all signs need to be present to make the diagnosis, however, and if you find one, others usually turn up in the examination.

A mnemonic from the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (Table 2) represents diagnostic signs in patients with the excited or retarded forms.2 We recommend that you review an authoritative text (see Related resources) to understand catatonia’s psychopathology.2

Table 1

Common diagnoses of patients with catatonia

| Psychiatric |

|

| Organic |

|

Catatonia is caused by neurochemical abnormalities including low GABA activity in the frontal cortex, low dopamine (D2) activity in the basal ganglia, high glutamate—N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)—activity in the parietal cortex, or a combination of these.3-5 Catatonic signs occur when these neurochemical changes cause aberrant signals and trigger a neural circuit affecting the medial gyrus of the orbital frontal lobe, the lateral gyrus, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus, and thalamus (Figure).

Posturing occurs when the aberrant signal reaches the posterior parietal lobe. Patients’ bizarre and mundane postures in catatonia are maintained by “anosognosia of position.” For example, an individual does not know the position of rest for his arm, and it remains in an unusual position as if at rest.3

The PP goes on to influence the supplemental motor area (SMA), causing bradykinesia, rigidity, and other motor phenomena that catatonia shares with Parkinson’s disease. The SMA feeds back to the medial orbital gyrus, completing the neural circuit.3

Regions such as the anterior cingulate area (ACA) and amygdala (1AMG) — also may be recruited into the expanded circuit. ACA recruitment may cause akinetic mutism, and fear is a symptom of AMG recruitment. If the anterior hypothalamus is affected, malignant catatonia or neuroleptic malignant syndrome may occur.3,5

This neural loop demonstrates an integrated model of psychosis. It may help explain why catatonia responds to treatment with lorazepam, ECT, and other agents such as antipsychotics and NMDA antagonists.

Illustration for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY by Marcia Hartsock, CMI