Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

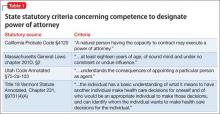

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8